Thymus

The thymus is the site of T-cell maturation. Thymic epithelial reticular cells attract thymocyte precursors and macrophages. The functional blood-thymus barrier consists of epithelial reticular cells, their basal laminae, and endothelial cells joined by tight junctions. This barrier keeps antigens in blood vessels from entering the thymus, preventing reaction with developing T-cells. The blood-thymus barrier is present in the cortex, but not the medulla.

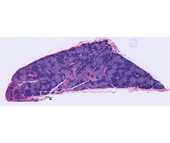

#26 Thymus, 21-month-old

This slide shows a section passing through a portion of one thymic lobe, surrounded by its thin connective tissue capsule. Thinner connective tissue partitions extend from the capsule and divide the thymic parenchyma incompletely into many angular thymic lobules, most of which are characterized by a peripheral dark cortex and a central paler medulla. The medullary tissue forms a continuous branching central core within each lobe.

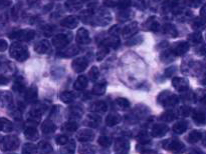

At higher magnification, the cortex may be seen as a dense layer of closely packed cells, mainly thymocytes. The fairly sharp demarcation of heavily stained small thymocytes in the cortex is more obvious than in the medulla. It is the round nuclei of these small thymocytes with very condensed chromatin that impart to the cortex a deeply stained appearance in this H&E preparation.

Careful examination of the parenchyma reveals larger, paler cells whose nuclei have a loose chromatin network and one or more prominent nucleoli, the epithelial-reticular. These large cells are interspersed between the densely packed small thymocytes. Some evidence of acidophilic cytoplasm may also be found around these large nuclei. Fewer of these epithelial cells are noticeable in the cortex because they are obscured by numerous thymocytes.

Careful examination of the parenchyma reveals larger, paler cells whose nuclei have a loose chromatin network and one or more prominent nucleoli, the epithelial-reticular. These large cells are interspersed between the densely packed small thymocytes. Some evidence of acidophilic cytoplasm may also be found around these large nuclei. Fewer of these epithelial cells are noticeable in the cortex because they are obscured by numerous thymocytes.

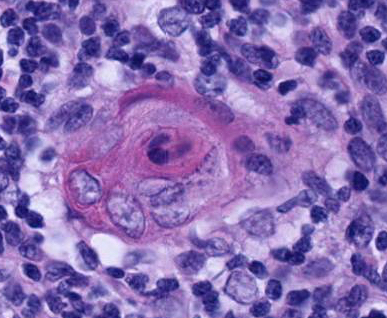

The medulla contains the same types of cells as the cortex but in different proportions. In the medulla, the thymocytes are reduced in number and the epithelial-reticular cells are much more prominent. The looser arrangement makes it possible to see the acidophilic cytoplasm of the epithelial-reticular cells which are arranged in structures called Hassall's corpuscles. These vary considerably in appearance and size within one thymus. Most of them have a deeply eosinophilic hyaline central mass surrounded by large concentrically arranged, epithelial-reticular cells.

The medulla contains the same types of cells as the cortex but in different proportions. In the medulla, the thymocytes are reduced in number and the epithelial-reticular cells are much more prominent. The looser arrangement makes it possible to see the acidophilic cytoplasm of the epithelial-reticular cells which are arranged in structures called Hassall's corpuscles. These vary considerably in appearance and size within one thymus. Most of them have a deeply eosinophilic hyaline central mass surrounded by large concentrically arranged, epithelial-reticular cells.

Note: The normal thymus lacks both lymphatic nodules and lymphatic or blood sinuses. Unlike lymph nodes, the thymus is not interposed in the lymph circulation and has no afferent lymphatic vessels.

#29 Thymus. Adult

Compare this section with slide #26. Involutional changes are evident in this section of adult thymus. As you have seen on the preceding slide, in childhood (from birth to 10 years of age) the thymus consists of closely crowded lobules of thymic tissue with thin connective tissue capsule and septa. At puberty (from about 11 to 15 years), the thymic parenchyma remains prominent but the interlobular septa become broader. Then the thymus begins to decrease in size, fat begins to appear, and changes known as "age involution" occur. From about 21 to 45 years, the adipose tissue becomes increasingly prominent and occupies a larger area than the parenchyma of the thymus. Notice that the cortex has lost density and the cortico-medullary boundary is obscured. The framework of epithelial-reticular cells of the cortex has collapsed and the cortical thymocytes have decreased in number, however the medulla may be seen to have suffered little change and large Hassall's corpuscles can still be readily identified. In older individuals, Hassall's corpuscles appear to be fewer in number.

Note: Despite postpubertal involution, the thymus remains a functional organ with recognizable cortex and medullary regions throughout life. The thymus may also undergo "accidental" or "stress involution" due to chronic illness.